From clunky Dutch workwear to controversial fashion favourite, Daisy Woodward explores why the distinctive wooden-soled shoe is a symbol of now.

The clog has long ranked among the world’s most divisive footwear. Beau Brummell, the original dandy and arbiter of men’s fashion in Regency England, is said to have had “a perfect abhorrence” of the protruding and protective wooden-soled shoe, according to his biographer, while 1970s Swedish pop sensations ABBA were such fervent fans that they started their own clog line.

“No clogs, please,” stiletto pioneer and clogophobe Christian Louboutin pleaded on the Fat Mascara podcast in September 2016, just days before British designer Christopher Kane unveiled his groundbreaking spring/summer 2017 collaboration with Crocs: geode-encrusted versions of the rubbery clogs formerly associated with gardening grandmothers. Then Dior creative director Maria Grazia Chiuri launched the Diorquake clog, an ode to 1960s sling-backs, officially galvanising the shoe’s 21st-Century high-fashion renaissance.

The clog is enjoying a 21st-Century high-fashion renaissance (Credit Getty Images)

Since then, the clog’s popularity has only increased: last spring, Hermès released an elegant version of the shoe it deemed “utility meets sensory pleasure”, which sold out almost instantly. In September 2021, Crocs announced that its sales are predicted to double by 2026. Elsewhere, independent clog brands like Santa Venetia and No. 6 are offering fresh, style-forward takes on the protective footwear once relegated to the realms of farming and factory work, proving its surprising, seemingly endless potential for reinvention.

The clog’s exact origins are unknown – wooden shoes made excellent firewood – but its ancient predecessors include Roman calcei (shoe-boots, designed for outdoor walking) and Japanese Geta (an elevating flip-flop-clog hybrid). The earliest surviving example of the traditional Dutch clog or klomp, meanwhile, dates back to early 13th-Century Amsterdam, where shoes carved entirely from wood became commonplace among labourers as a cheap and effective means of protection and warmth.

By 1570, the first guild of klomp makers had been established in Holland, attesting to the proliferation of skilled craftspeople who had now made hewing shoes from single blocks of split-resistant wood, like alder, beech and sycamore, their profession. By this point, wooden-soled shoes of varying forms had been adopted by workers across Europe, from the Spanish albarca to the French sabot, and remained the most popular mode of protective footwear well into the age of the Industrial Revolution. Indeed, there is a possibly apocryphal myth that the term sabotage stems from sabot-sporting French factory workers who either used their discarded clogs to wilfully damage machinery, or who proved less efficient than their leather-shoe-wearing contemporaries, depending on which account you choose to believe.

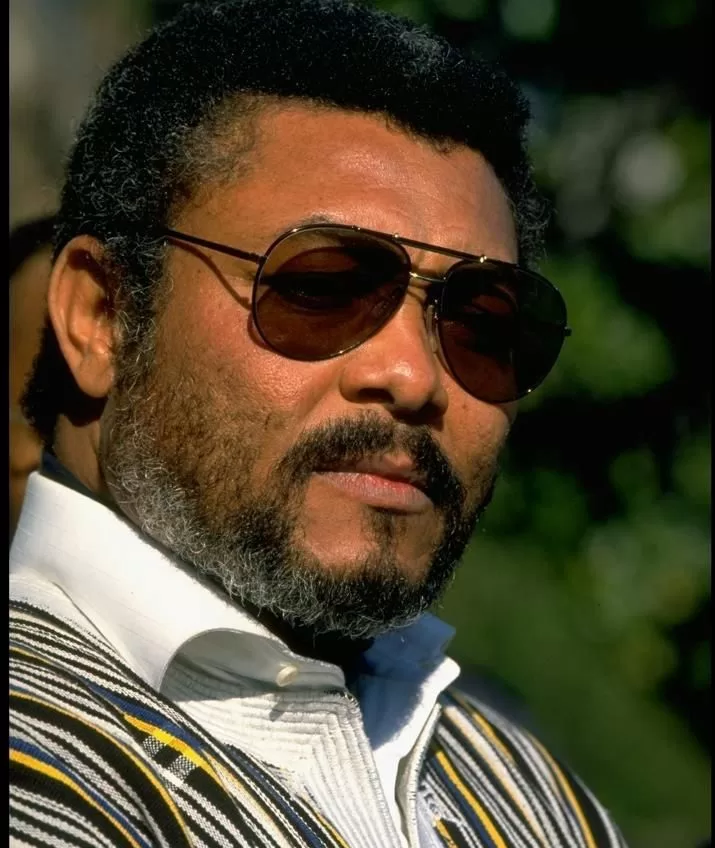

Wooden clogs were an important element of traditional Dutch attire for both men and women (Credit: Getty Images)

Clogs arrived in Britain as early as the 1300s, but unlike the all-wooden Dutch versions, they consisted of wooden soles and leather uppers, explains Jeremy Atkinson, England’s last traditional clog maker. “That’s because British soil is much more abrasive, I believe, so leather fared better.” Clogs were the footwear of choice for British workers throughout the Industrial Revolution, because “they were durable, cheaper than shoes, and better in both the wet and the heat – they’re very absorbent,” Atkinson tells BBC Culture. Their popularity only began to wane in the mid 1800s, “when hobnail boots became more affordable”.

Nevertheless, the clog could still be found in the cotton mills and mines of 19th-Century northern Britain, where it doubled as dance shoe with the arrival of clog dancing. This started among labourers, who would create rhythmic, clacking dances with their wooden soles to allay boredom and dispel the cold, and soon emerged as a popular form of music hall entertainment preceding tap dancing. (Tap wunderkind Charlie Chaplin began his career as a clog dancer.)

Opting for a clog over more conventionally fashionable footwear is a sign of self-certainty, and aligns with the rise of “uglycore” fashion

It wasn’t until the 1960s and 70s however, that clogs became a widespread fashion statement. This particular iteration derived from the Swedish clog or träskor, a backless shoe with a wooden sole and leather upper with a square toe. “These were originally designed as a sort of yard boot that you could slip on with a woolly sock to go out and feed the animals, and then slip off again,” Atkinson explains.

The clog was particularly fashionable in the 1970s – and the comfy, clunky shoe is now once again sought-after (Credit: Alamy)

The clog’s all-natural materials, and the fact that they remained at least partially handmade, appealed to the back-to-nature attitude of 1960s counterculture. In the 70s, the shoe’s clompy sole and angular silhouette paired perfectly with the decade’s trend for long flowing skirts and flared jeans, prompting the embrace of Swedish-style clogs by brands like Gucci and MIA, who playfully reinterpreted them for the platform-loving youth.

Since then, the clog has fallen in and out of favour among the sartorially-inclined. The 1990s marked the original rise of the pretty/ugly shoe, the clog very much included, which saw orthopaedic-style footwear repurposed as an expression of what Vogue terms “an ironic, detached, ‘come as you are’ attitude that thumbed the nose at convention, polish, and glamour”. The 2000s also prompted a renewed, albeit temporary, interest in clogs when Dutch design duo Viktor and Rolf debuted traditionally decorated, high-heeled klompen on the spring/summer 2007 runway, followed by Karl Lagerfeld’s towering take on träskor for Chanel’s spring/summer 2010 collection three years later.

The clog comeback

Yet the current clog mania, which has been steadily gaining traction since Kane’s Croc collaboration, seems to be more aligned with the far-reaching 1970s craze – and has spawned a whole host of clog iterations and reinterpretations. Scandinavian brand Swedish Hasbeens, which launched in 2006 offering handmade takes on classic 70s styles, has been enjoying a resurgence in popularity. And the past year has seen some of fashion’s most influential names put their own distinct spin on the shoe, not least Molly Goddard’s maximalist spring/summer 2021 collaboration with UGG, which included a platform clog in eye-popping colourways.

Among recent fashion favourites is designer Molly Goddard’s platform clog, a collaboration with UGG (Credit: UGG x Molly Goddard)

In October 2021, global fashion search platform Lyst reported that searches for clogs have increased by 124% compared to the previous year, while searches for wooden clogs, in particular, were said to be up by 65% month-on-month. The most coveted styles range from the more practical and affordable – Birkenstock Arizonas and MIA Almas – to high-fashion heeled offerings by Chanel and Dolce & Gabbana.

So what is it about the clog that particularly appeals to a 2020s audience? This is the question BBC Culture posed to Lauren Mechling, senior editor at US Vogue and founder of @thecloglife, an Instagram account dedicated to all things clog. “There are multiple factors that have converged into a perfect storm of the clog’s comeback,” she writes over email, “the first being that, in our post-#girlboss moment, feminism isn’t just in fashion, but is ingrained in the culture like never before”. As a woman, there is a spirit of transgression to wearing a clog, she explains, because those who do so “reject the notion that heels, which have long been believed to be the visually pleasing footwear, are what is in order if one wants to look pulled together”. This could equally be said of other gender identities: opting for a clog over more conventionally fashionable footwear is a sign of self-certainty, and aligns with the rise of “uglycore” fashion, 2022’s own brand of Gen-Z punk style. Mechling also notes that the pandemic has, to some degree, eviscerated the uncomfortable footwear that was once an integral part of a working wardrobe – “so more and more late adopters have bought a pair”.

Uncomfortable clogs defeat the entire point of clogginess, which is liberation and self-celebration – Laura Mechling

The contemporary shift towards comfort certainly seems to be an integral factor in the clog’s return – 2021 could be described as a year of comfortable glamour in fashion, tailored towards our cautious re-emergence from lockdown life. And clogs, it turns out, are the ideal “transitional shoe” according to Tobias Klaiber, CEO of Scholl Shoes, the footwear brand that invented the calf-toning, clog sandal, the Scholl Pescura, in the 1950s. Like Birkenstock, which debuted its Boston clog in 1979, and Crocs, which unveiled its rubber boating slip-ons in 2001, Scholl has been producing clogs non-stop since its inception, and is now “surfing the wave” of the shoe’s renaissance.

Just as Birkenstock and Crocs have embarked on many high-fashion collaborations of late, with designers like Valentino Garavarni and Jil Sander (Birkenstock), and Balenciaga’s Demna Gvasalia (Crocs), Scholl recently partnered with Kate Spade, and has just released a bold new clog collection, titled Scholl Iconic, reimaging their Pescura clogs and sandals for a 21st-Century audience. This includes tartan and faux fur in abundance, and a focus on sustainability – another defining element of the wooden-soled shoe’s contemporary appeal, according to Klaiber. The collection’s tagline is “haute comfort” which, the CEO says, points to the fact that “fashion and comfort don’t have to exclude each other”.

The recent revival of interest in clogs has led to some inventive designs, including Santa Venetia’s collaboration with Panache (Credit: Santa Venetia)

Santa Venetia x Panache clogs

This sentiment was the driving force behind the inception of California clog brand Santa Venetia which began in 2017. “I always wanted to be into clogs, but they never quite fit my aesthetic,” says co-founder Gemma Greenhill over the phone, explaining that it was a friend’s pair of 1960s clogs with entirely embroidered uppers that swayed her.

These were the shoes that formed the template for Santa Venetia’s first design, Greenhill notes, “and since then we’ve been creating clogs that are a bit unexpected, just a little bit different from your regular clog”. This includes a collaboration with Panache, featuring hand-painted sushi, fruit, martinis and hot dogs, and an elevated take on the rubber-soled nursing clog, a comfort-forward design that Greenhill notes was 2021’s most popular style. “I think that, right now, people want to have a bit of fun within the parameter of practicality.”

Indeed, Mechling affirms that the only clogs worth investing in are ones that feel good. Her other top choices include California label Beklina’s ribbed clogs, which she describes as “powerful and ladylike” and New York brand No. 6’s shearling-lined boots (“a bubble bath for the feet”). “Uncomfortable clogs defeat the entire point of clogginess,” she adds conclusively, “which is liberation and self-celebration”.