A legal opinion written by A. A. Bright, a lawyer, has argued that Justice Kwasi Anokye Gyimah – the judge who ruled that the GHS217-million Opuni-Agongo case start de novo, after having taken over from retired judge, Justice Clemence Honyenuga – had grounding, at common law, for his ruling, which was subsequently unanimously overturned by the Court of Appeal, whose panel comprised P. Bright Mensah, Jennifer Abena Dadzie and Dr. E. Owusu-Dapaa on 31/07/2023.

The Court of Appeal then ordered that the trial High Court, which had again been differently constituted, adopt the proceedings and continue the trial from where Justice Honyenuga left off.

In his opinion piece, however, A. A. Bright wondered: “… Can a new judge who inherits a criminal case for which evidence has already been partly taken, adopt the proceedings and continue the hearing therefrom?”

The author recalled that the Court of Appeal excoriated Justice Gyimah for declining the invitation by the Attorney General to adopt the proceedings, noting that Justice P. Bright Mensah, who delivered the lead opinion, described the decision of Justice Gyimah as “uninformed”.

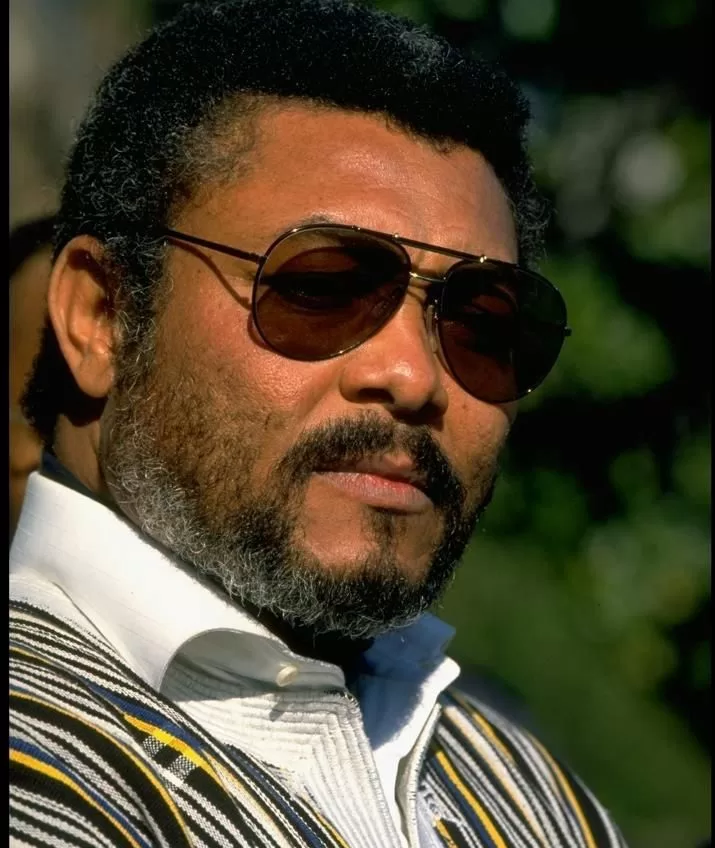

“Was the decision of Gyimah J really legally uninformed?”, the authored asked, and examined “the reasoning of the Court of Appeal to see whether it is sound, coherent, logical and satisfactory”, since, he noted: “To a lawyer, the grounds upon which decisions are based are important than the decision itself”, referencing ‘Rockson Vrs. Armah: a Case of Caveat Emptor, Caveat Venditor or Neither?’ [1978] VOL. XVUGLJ 168, by the erudite J. E. A. Mills, who later became President of Ghana.

The author asserted that at common law, “the settled practice in criminal proceedings is that when a new judge inherits a criminal case, he automatically starts the case de novo, no matter the stage of the proceedings or trial”.

“The rationale is that, in a criminal trial, the judge is required to examine the totality of the evidence on the record, including assessing the credibility of witnesses based on their demeanor before reaching his decision. The judge must thoroughly evaluate all the material pieces of evidence on the record to satisfy himself that his decision is reasonable, having regard to the totality of the evidence. The Supreme Court of Ghana, in 1993, reaffirmed the common law position that a partly-heard criminal case could only be heard de novo when a new judge took over the trial”, referencing the Republic Vrs. Adu-Boahene and Another [1992-93] 2 G B R 452.

In that case, he said the Supreme Court, speaking through Amu Sekyi JSC had the following definitive words regarding trials de novo in criminal cases: “A case is partly heard when a hearing on the merits had begun, that is, when the court or judge, has started to enquire in to the substance of the cause or matter brought before him. In criminal matters, such steps as taking the plea of an accused person, listening to and recording the facts alleged against him and which the prosecution intend to prove at the trial, do not constitute a hearing of a complaint. The hearing begins, and the case becomes partly-heard only when the prosecution begins to adduce evidence to prove the charge. Before then the case can be transferred to another court or judge for hearing, but once the hearing starts, this can only be done if the trial is aborted and a fresh hearing ordered”.

The author argued that the words of the Supreme Court per Amua-Sekyi JSC are, thus, loud, clear and authoritative in reaffirming the settled common law practice that a partly-heard case in a criminal matter can only be heard de novo when the court is differently constituted.

“The lawyers of the accused/respondents could not bring to the attention of the Court of Appeal the holding of Amua-Sekyi JSC in the above case. Be that as it may, I am at a loss as to why the Court of Appeal did not advert their minds to the decision in Republic Vrs. Adu-Boahene and Another. (Supra). It has often been said that the law is in the bosom of the judge and, so, if counsel for the accused/respondents could not bring the above mentioned authority to the attention of the Court of Appeal judges, the judges were duty bound to look for it and apply”.

“If the judges of the Court of Appeal had been extremely diligent, they would have adverted their minds to this very important authority. The decision by Gyimah J to start the trial de novo, therefore, has legal basis. His decision is anchored on binding case law and, therefore, well informed. The description of the decision of Gyimah J by P. Bright Mensah J .A . as ‘uninformed’ was completely unwarranted by any rule of law. Gyimah J’s ruling could not be reasonably faulted”, the authored put forth.