Iran has declared it will no longer abide by any of the restrictions imposed by the 2015 nuclear deal.

In a statement it said it would no longer observe limitations on its capacity for enrichment, the level of enrichment, the stock of enriched material, or research and development. The statement came after a meeting of the Iranian cabinet in Tehran. Tensions have been high over the killing of Iranian General Qasem Soleimani by the US in Baghdad. Reports from Baghdad say the US embassy compound there was targeted in an attack on Sunday evening. A source told the BBC that four rounds of “indirect fire ” had been launched in the direction of the embassy. There are no reports of casualties. Hundreds of thousands turned out in Iran on Sunday to give Soleimani a hero’s welcome ahead of his funeral on Tuesday. Under the 2015 accord, Iran agreed to limit its sensitive nuclear activities and allow in international inspectors in return for the lifting of crippling economic sanctions. US President Donald Trump abandoned it in 2018, saying he wanted to force Iran to negotiate a new deal that would place indefinite curbs on its nuclear programme and also halt its development of ballistic missiles. Iran refused and had since been gradually rolling back its commitments under the agreement. Earlier on Sunday, Iraqi MPs passed a non-binding resolution calling for foreign troops to leave the country after the killing of Soleimani in a drone strike at Baghdad airport on Friday. About 5,000 US soldiers are in Iraq as part of the international coalition against the Islamic State (IS) group. The coalition paused operations against IS in Iraq just before Sunday’s vote. Mr Trump has again threatened Iran that the US will strike back in the event of retaliation for Soleimani’s death, this time saying it could do so “perhaps in a disproportionate manner”.Iran rolls back nuclear deal commitments

Reading Time: 5 mins read

Recent Posts

- Cynthia Morrison faces jail term over contempt charges

- Survey: NPP’s Chris Arthur projected to win Agona West by landslide

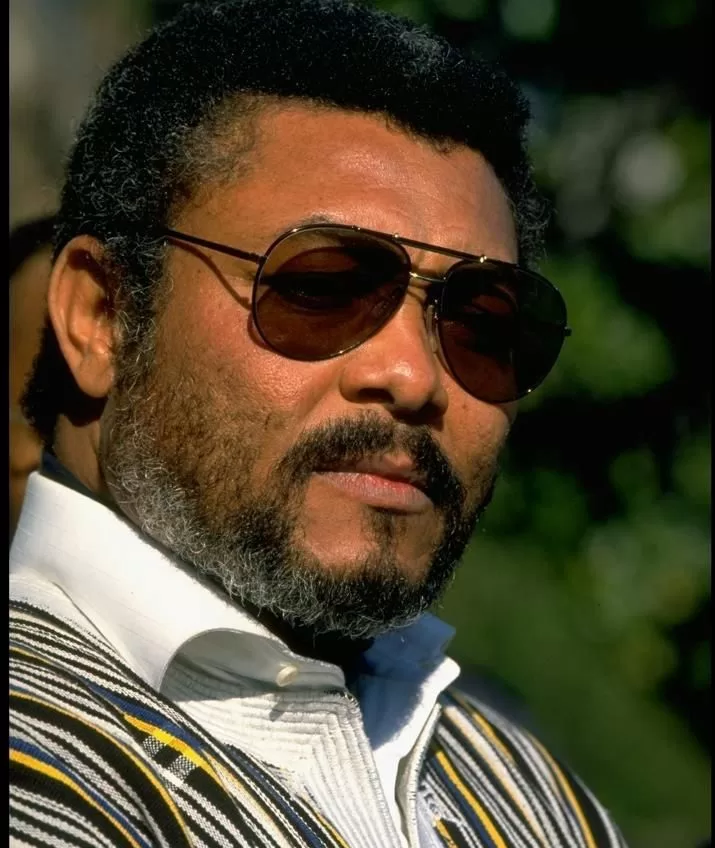

- President Jerry John Rawlings – Four Years On

- Friday, November 8 not a public holiday – Interior Ministry

- Tragic: Speeding NDC vehicle kills the only child of a mother at North Dayi

- Pay NABCO trainees if you care about Ghanaian youth – Mahama tells Bawumia

- Suspend planned strike – FWSC pleads with CLOGSAG

- Some lawyers sacrifice ethics for ‘cheap’ political gains – Attorney-General

Popular Stories

-

Cynthia Morrison faces jail term over contempt charges

-

Survey: NPP’s Chris Arthur projected to win Agona West by landslide

-

Friday, November 8 not a public holiday – Interior Ministry

-

Agona West MP deserts NPP, promises ‘doku’ to women as she goes independent

-

University staff declares nationwide strike

ABOUT US

Newstitbits.com is a 21st Century journalism providing the needed independent, credible, fair and reliable alternative in comprehensive news delivering that promotes knowledge, political stability and economic prosperity.

Contact us: [email protected]

@2023 – Newstitbits.com. All Rights Reserved.