The outcome of Friday’s UN Security Council vote on the future of the peacekeeping force in Mali is not in doubt: they have little choice but to terminate what has been the most deadly of all such UN operations around the world.

Over its more than 10-year deployment, some 187 peacekeepers have lost their lives.

However, it is not the casualty toll that is driving the UN out of Mali. It is the country’s military regime that is insisting the 12,000 international troops must depart – despite a desperate security crisis that shows no sign of fading away.

Once the UN peacekeepers have departed, Mali will be even more dependent on the Russian mercenary Wagner group, which is thought to have 1,000 fighters in the country, for security back-up.

Across northern and central regions of Mali, a vast country that extends from tropical West Africa deep into the Sahara Desert, jihadist armed groups stage regular attacks.

Despite Wagner’s fearsome reputation, there must be questions about its effectiveness in fighting the militants, even if manpower is boosted with extra fighters redeployed from the war in Ukraine.

The recent falling out between Russia President Vladimir Putin and Yevgeny Prigozhin, the leader of the mercenary outfit, may raise questions about the exact arrangements under which these forces are deployed.

For Russia’s president their presence is a useful way of needling France and the US and bolstering the Russian footprint in West Africa.

But Wagner will not have the scale of air-strike power, armoured units and logistical support, backed up with US satellite intelligence, that was at the disposal of the French force Barkhane – which pulled out last year after the breakdown of trust between Mali and the former colonial power.

Wagner units seem more likely to prioritise the holding of a few key bases, from where they may venture out on raids and patrols, rather than an overall strategic push.

The 11 months during which Mali has relied on Wagner rather than French support have seen jihadist groups intensify their activities and extend their reach.

Once the UN has also left, that trend could accelerate, while the mercenaries’ hard-line approach could further alienate Tuareg and Peulh (also known as Fulani) pastoralist communities.

Tensions between farming and livestock herding communities have already added fuel to the violence in parts of central Mali, where the fertile inland delta of the River Niger should be West Africa’s rice basket.

Amidst the insecurity, more than 1,500 schools are closed and local economic life is badly disrupted. The Malian state and basic public administration and essential services are entirely absent from many parts of the north.

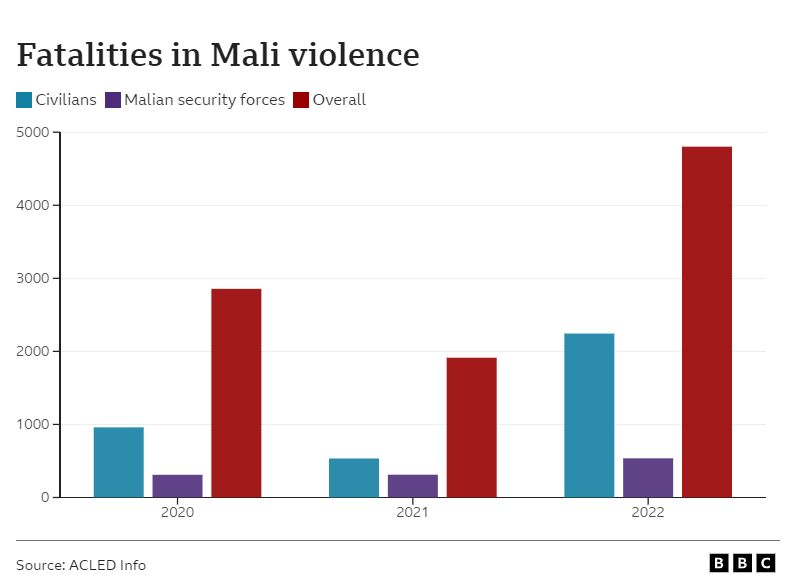

The monitoring group Acled reports that 1,576 people were killed in 682 incidents so far this year.

Conditions are particularly bad in the north-east, where thousands of civilian villagers have now taken refuge in camps surrounding the small desert town of Ménaka. It is communities up north that are more likely to suffer from the UN mission’s withdrawal.

The army claims some recent successes but in reality is struggling to cope. Even the fringes of Bamako, the capital, hundreds of miles to the south, have been attacked.

Mali’s military ruler Colonel Assimi Goïta – who seized power in a coup in August 2020 – has been demanding that the UN force, known as Minusma, take on a much more aggressive anti-terrorist role, in support of the national army.

But the UN troops have had a peacekeeping mandate – to shield civilians from militant attack, support basic public services and humanitarian relief and underpin a 2015 agreement. Under that deal, ethnic Tuareg separatists in the north agreed to remain within a united Mali – in return for decentralisation of power to the local level.

Aggressive anti-terrorist fighting was in fact the job of France’s Barkhane unit, whose departure last August was largely blamed on Mali’s decision to invite Wagner into the country.

Yet still frustrated at Minusma’s reluctance to back its muscular agenda, Mali has now decided that the UN force must also now get out “without delay”, though France’s draft resolution suggests it will take six months.

But there is more to this wrangle. Col Goïta is also upset that the UN troops will not fall into line in support of his determination to reassert the national sovereignty of the central government and his lack of interest in properly implementing the decentralisation promised under a 2015 peace agreement with northern Tuareg rebels who had been fighting for Azawad, an independent homeland in the Sahara.

Moreover, relations with not just the UN but several Western governments and also many of Mali’s regional neighbours have been soured by mistrust and resentment for the past two years.

In September 2021 Prime Minister Choguel Maïga accused France at the UN General Assembly of abandoning the country “in mid-air”, even as French troops continued to die in the campaign against the jihadists. Within months the government had turned instead to Wagner.

Fellow members of the regional body, Ecowas, already exasperated by Col Goïta’s procrastination over a timetable for restoring democracy, condemned the presence of the mercenaries as a threat to the security of the whole region.

Then over the course of the next 18 months, the government imposed progressively more impediments to the operation of the UN force by, for example, delaying permission for troop rotations and by limiting the UN’s rights to fly – seemingly to prevent oversight of the areas where Wagner’s men were active, and even where the lives of injured troops were at risk.

Moreover, once the French combat troops had gone, the peacekeepers were also more vulnerable to attack.

Last July, amidst a continuing dispute with Ecowas over the transition timeframe, Mali arrested 49 soldiers from Ivory Coast who had arrived to guard UN premises under a longstanding arrangement and accused them of spying. All but three remained in detention until January, when they were finally freed after long, drawn-out negotiations.

As operating conditions for the UN force became progressively more difficult, Ivory Coast, Germany, the UK and Sweden announced plans to withdraw their contingents.

But the final breakdown in relations came with the publication this May of a UN investigation into the killing of civilians at the village of Moura in central Mali in March 2022.

Although the junta refused to let Minusma visit the site, the UN force managed to reach nearby communities, interview survivors and obtain proof of the identity of 238 victims.

Its verdict was damning: more than 500 people had been killed in Moura in March 2022 by the army and allied “foreign” fighters – a clear allusion to Wagner.

The government responded with fury, threatening a judicial enquiry against the members of the investigation team. It accused them of spying, plotting and threatening state security.

After this, its demand for the rapid winding-up of the UN force could hardly come as a total surprise.

Moreover, anti-Minusma opinion had been mobilising for months.

“It is the entire Malian nation together that is rediscovering itself,” said one contributor to a recent TV discussion show.

The TV show presenter himself described the campaign to press for the departure of the UN force – the bulk of which is made up of African soldiers – as “yet another battle against the oppressor and the West”.

Col Goïta has just secured the backing in a referendum for a new constitution strengthening presidential power and authorising military leaders to run in elections planned for next year. With the UN out of the way, he will have a freer hand to drive forward with his agenda.

However, ordinary Malians, particularly in the fragile centre and north, may miss the UN force. While it proved unable to halt jihadist attacks, it did provide a level of containment, ensuring an essential minimum of calm and stability in key towns, so that basic services, administration and welfare could operate.

And its presence at least kept alive the deal with northern groups who have lost all faith in the military government.

With the UN peacekeepers gone, parts of the north where the army and Wagner struggle to make themselves felt may actually drift even further towards de facto autonomy.

Far from Bamako’s heated city politics, everyday life for many communities will probably just get even more difficult.

Paul Melly is a consulting fellow with the Africa Programme at Chatham House in London.