Yesterday, the President of Ghana announced that he has engaged the local affiliate of KPMG, one of the “Big Four” global professional services firms, to conduct a two-week investigation into the “SML affair”.

SML is the name of a hitherto unknown entity created in 2017 by timber merchant, Evans Adusei, and a relative just before it entered into discussions with various state agencies to offer “revenue assurance” services.

A mysterious new entrant

The company popped into Ghana’s public consciousness following a documentary and a series of investigations by MFWA-backed investigative outfit, the Fourth Estate. Away from the limelight, activist think tank ACEP has been probing the SML affair as part of an elaborate review of “revenue assurance” programs in Ghana for more than a year. Alongside broader public financial management (PFM) work in the natural resources sector by another Ghanaian activist think tank, IMANI, ACEP’s careful unpacking of the situation has uncovered multiple redundancies and duplications of efforts costing the Ghanaian taxpayer tens of millions of dollars for little value in return.

The thrust of the SML arrangements is summarised below.

SML has been given a series of contracts to block illegal tax evasion and tax avoidance schemes in Ghana since 2019. Beginning with a contract to support the Ghana Revenue Authority (GRA) to detect invoice fraud, SML’s tentacles soon spread to the downstream petroleum sector, where it is supposed to assist GRA in fighting under-declaration of fuel volumes and, by extension, taxes collected by the fuel marketers from consumers on behalf of the government.

In June 2023, the Finance Ministry wrote to the GRA to advise an expansion of the scope of these contracts to cover minerals exported by Ghana, from which roughly 70% of export revenues are derived.

None of these contracts were competitively awarded. No serious due diligence was conducted on the capacity of SML to deliver any serious value, which is not surprising considering its total lack of track record in this area until it secured the contract. SML’s beneficial owner and principal, the timber merchant mentioned earlier, had no prior Information Technology (IT) business experience either, even though IT is a central plank of the SML value proposition.

The downstream petroleum regulator, the National Petroleum Authority (NPA), has signed multiple contracts with companies such as Nationwide Technologies (an agent/affiliate of Texas-based Authentix Inc) and Rock Africa, a company led by former e-waste consultant, Francis Gavor, all of which are meant to fight fraud, adulteration, and under-declaration etc. GRA could very well have engaged the NPA to institute a data-exchange regime.

SML was, at the time investigations commenced, earning 21 million Ghana Cedis (GHS) a month (or ~3.5 million 2020 dollars) from a pricing regime which granted the company 5 Ghana Pesewas (5 GHP) for each litre of product covered.

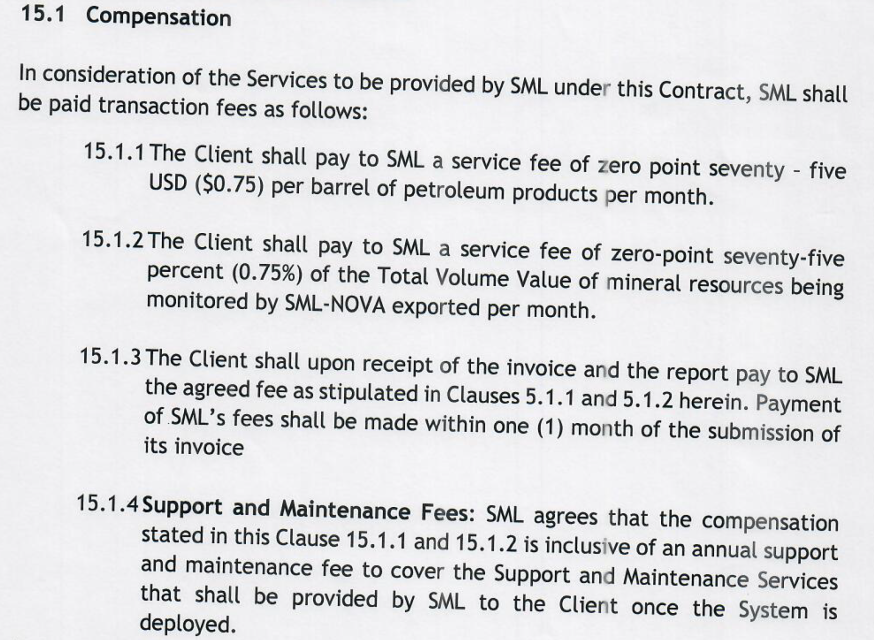

In the expanded contract scope, SML will henceforth earn 0.75% of the total “volume value” of all mineral resources exported out of Ghana. It will also earn $0.75 for each barrel of “petroleum products” sent overseas from Ghana’s oilfields.

Why the SML deal is a scandal

There are many things wrong with the SML affair. The procurement abuses are obvious: how did the government learn about the magical revenue assurance mojo of this timber merchant and his new entity to warrant such massive trust? Why did the ever-pliant Public Procurement Authority, long discredited after its previous boss was found engaging in his own procurement shenanigans, accept the eligibility of this deal for sole sourcing?

The pricing is atrocious: SML gets a share of Ghana’s most prized revenue streams for fighting fraud with no clear parameters for measuring the progress of that fight.

And the underlying logic of the arrangement, especially in the context of multiple state agencies spending precious public resources to pursue the same objectives, is hopeless.

The government’s defence

The government has mounted a spirited defence of the contract.

The heart of the GRA’s defence rests on a purported improvement seen in revenue numbers since SML volume monitoring began. We quote the GRA statement verbatim below.

The work of SML over the period has led to a significant increase in the figures reported in the downstream petroleum sector, from an average of 350 million litres per month in 2018 and 2019, to 450 million litres per month from 2020/2021. This represents over a thirty- three percent (33%) increase in volume reporting and an average of an extra 100 million litres per month at a levy rate of GH¢1.44p. The extra revenue variance gained for the two (2) years will exceed GH¢3billion. This performance is attributable mainly to the introduction of ICUMS and SML systems.

There is, unfortunately, no grounding to this strange analysis.

The SML defence “falls flat”

For the argument to be sustainable, proof has to be shown that SML’s interventions have led to an uptick in volumes recorded over and above the historical trend of increases over time. What the data instead show is a correlation between volume increases/decreases and exogenous economic factors.

Take, for instance, the fact that more residual fuel oil (RFO) was consumed in Ghana in 1999 than in 2022. The demand for this fuel was historically boosted beyond its traditional importance in the marine industry due to its use in legacy equipment in the industrial sector. As other petroleum products supplanted RFO, however, volumes dropped significantly. Following a very similar trajectory, the volume of kerosine consumed in Ghana in 2022 was 30 times less than that consumed in 1999, obviously, in part, because of the rise of LPG. Indicative of the challenges in Ghana’s fishing sector, premix fuel consumption has halved over the last ten years. Aviation fuel consumption in 2012, seven years before the SML contract was signed, was nearly 10% higher than in 2020, the first year after the SML monitoring regime went into effect. It is not hard to understand why: COVID.

Clearly, there are broad and exogenous, factors impacting fuel demand, consumption, and, thus, volumes that can be easily, and mistakenly, subsumed under the ambit of regulatory monitoring and whatever magic SML claims to be performing in the sector.

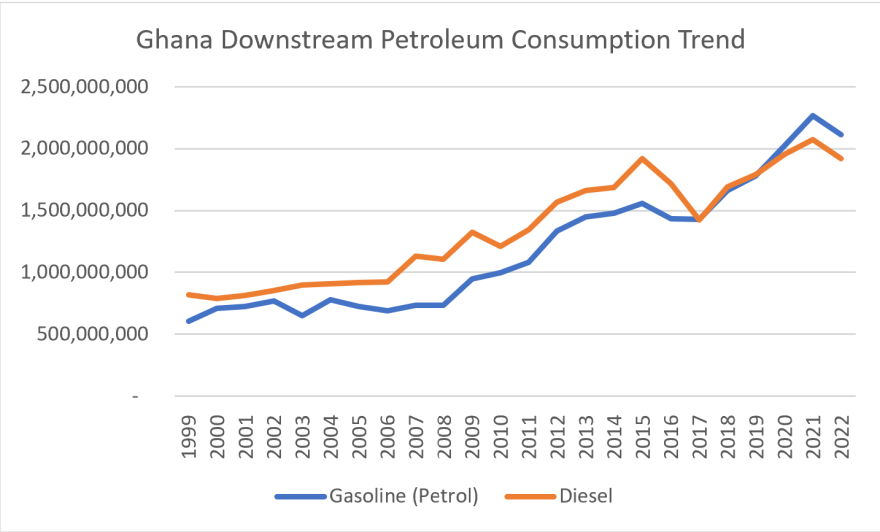

Focusing only on gas oil (“diesel”) and gasoline (“petrol” or “premier motor spirit”), the main fuels consumed in the downstream sector, elicits the same trend: consumption rises steadily, punctuated mainly by factors exogenous (external) to the fuel industry and its regulation.

For example, petrol consumption was steady for much of the decade between 1999 and 2009 until the completion of HIPC, the discovery and commencement of oil production, and the completion of the 2015 – 2019 IMF program, combined to trigger an economic mini-boom. The surge in consumption continued until dumsor (Ghana’s perennial power crises) peaked in 2015, leading to a major cratering of volumes. The mini-boom created by the end of dumsor, the completion of the IMF program, and the return to the Eurobond market with a vengeance, account for the last spurt of growth that just ended in 2022.

The SML value-addition scam

Only basic arithmetic is required to establish the groundlessness of the “volume increase” proof adduced by the government in support of the SML intervention.

As evidence that the SML contract has had no effect on things, we can compare the volume increases since the SML monitoring regime went into effect with previous growth phases. Between 2008 and 2015, for instance, volumes increased by more than 112%, on the back of a compounded annual growth rate of nearly 11.5%. The post-SML situation, on the other hand, saw volumes increase by 18.5% between 2019 and 2022, on the back of a mere 4.34% annual growth rate (the reader should see this in the slope of different segments of the above curve). In simple terms, volumes have increased by far less in the post-SML era than it did during previous eras.

SML may deserve to be surcharged not compensated

The obvious question that arises from the data is whether the fall in volumes that has been experienced between 2021 and 2023 should be attributed to the incompetence of SML. If not, why?

Petrol and diesel volumes dropped 7% and 8%, respectively, between 2021 and 22 due to a combination of economic slowdown and fuel price hikes. In fact, diesel volumes were lower in 2022 than in 2020, the year COVID-19 shut down parts of the economy. The data for 2023, so far, shows that petrol and diesel volumes will be lower than in 2021.

Should these statistical facts be taken to mean that the SML monitoring regime is losing the country money? Should a surcharge be applied based on an extended application of the same logic of “performance attribution” in the government’s defence of the contract?

The billion-dollar scope-extension

Considering the above analysis of SML’s current work in the downstream sector, it naturally follows that the extension of the contract to cover 70% of Ghana’s exports derived from the minerals and petroleum sectors will lead to a similar misattribution of value, and will amount to, therefore, to a total rip-off of the country.

First, there is no historical trajectory baseline computed in the contract that would enable the determination of “additional volumes” attributed to SML’s work. Moreover, there is no mechanism to determine how to exonerate/absolve SML if volumes fall and when or how to surcharge them for real underperformance in any given year. The so-called “value for money audits” mentioned in the contract are not defined, and, given the general feel of the contract, may well be undefinable.

From the analysis conducted by IMANI and ACEP, depending on certain developments in the minerals and petroleum sector, SML’s cumulative earnings from the contract could exceed $1 billion over the horizon anticipated by the contract. These developments include the activation of new oil fields; prospects of refined petroleum exports (for example, if Sentuo fully comes onstream); continued surge in gold production; effective local refining of minerals such as bauxite and lithium, thereby increasing their value in light of the contract’s construal of “volume value”; and the discovery of new minerals or commercialisation of currently unexploited deposits.

As has been amply demonstrated, such earnings, in the current framing of the engagement, would be attributable to SML regardless of which exogenous forces (such as local value addition, economic cycles, new discoveries, global commodity prices, global commodity demand etc.) are truly driving the increase in export or consumption volumes. Clearly, the entire arrangement is illogical and cannot be sustained by any rational justification.

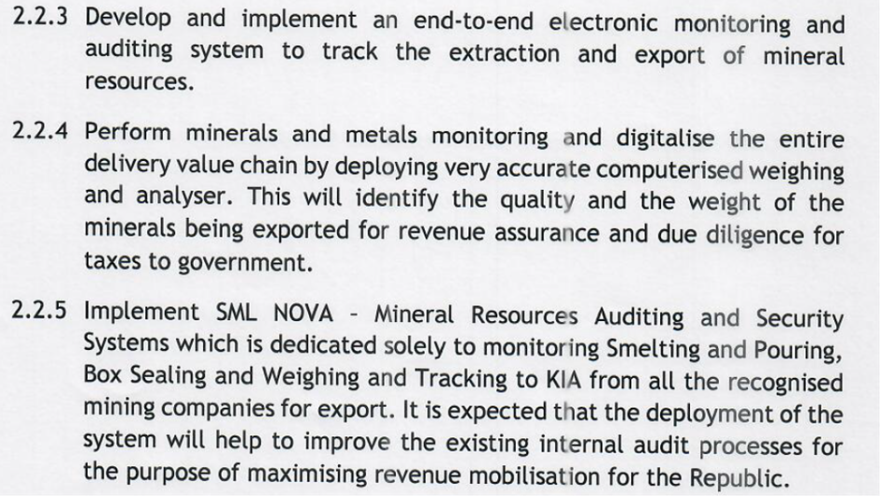

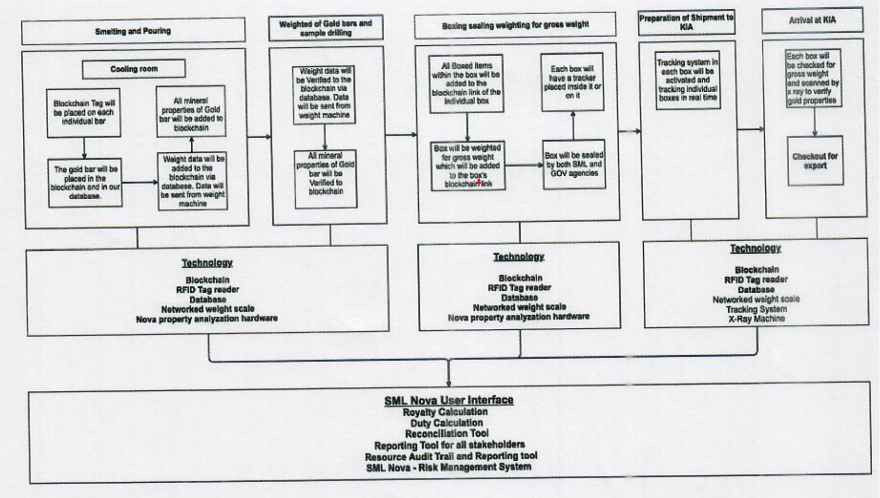

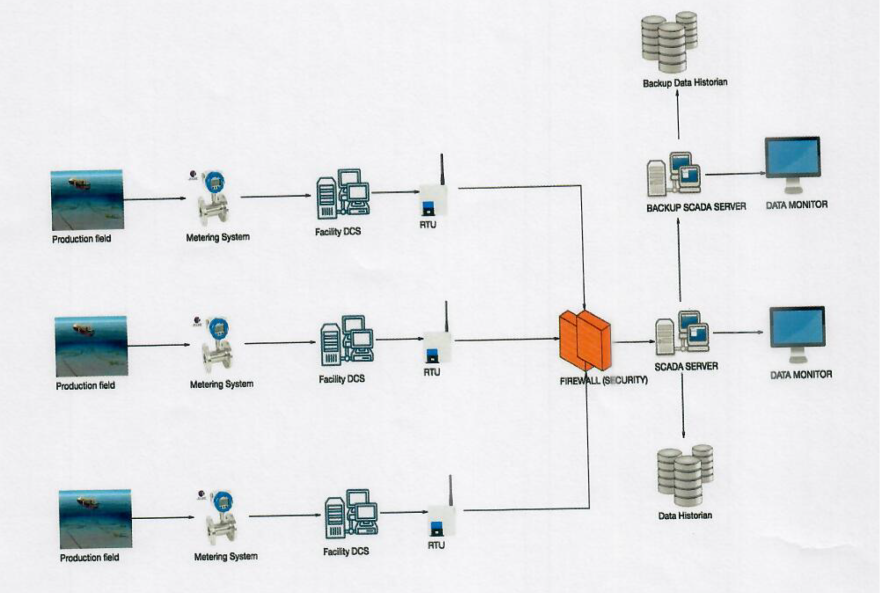

SML’s Solution Architecture

SML has protested the Fourth Estate’s coverage and pushed back against the analysis of IMANI and ACEP. It contends that its upfront investments in cutting-edge technologies and skilled staff entitles it to hundreds of millions of dollars of Ghana’s money.

The scope of the planned investments can be summarised by reference to section 15 of the amended and restated contract signed in 2023.

The software, sensors, networks and skillsets being promised by SML are valued in cursory fashion at ~$75 million in two tables found in the appendices of the contract.

The government did not perform any valuation of these assets prior to executing the agreement. Given that SML retains the full intellectual property of all these systems, they are meant to be applied to the assignment on a mere subscription basis during the term of the contract. Presumably, then, the contract could have been drafted on the basis of the value of such subscriptions to the procuring entity. It is completely perplexing how the leasing of agent-operated software suddenly translated into a design to share revenues accruing from the country’s fuel consumption and mineral exports.

Besides the total lack of auditability of the financial numbers involved, the technical specifications of the software and instruments being offered in this billion-dollar agreement are also vague to the point of uselessness. Below, we reproduced the entire schema for the reader’s own appreciation.

Solid minerals monitoring suite architecture. Copyright: SML

Upstream petroleum monitoring suite. Copyright: SML

First, as any analyst with any experience whatsoever in any technical field would agree, these “specifications” are meaningless. Even basic diagram legends, notations, and references are missing. The NITA enterprise reference architecture used in Ghana, and other elementary rulesets for IT design in the public sector, were all breezily dismissed for hurriedly cobbled together patchworks that convey no information about how the fancy blockchain technology SML says it will deploy to prevent the mining and petroleum companies from cheating Ghana will actually succeed where all other state agencies have failed.

In order not to bore the reader, this author will not delve further into the technological aspects of the proposed solution, as can be discerned from the diagrams. Suffice it to say that the proposed RFID-blockchain approach in the way it has been laid out betrays a woeful misunderstanding of how each of the interacting domains – blockchain, RFID, Xray, gold assaying, gold bar moulding, mineral weighing etc all work. In a proper investigation, the sheer incongruity of the architecture and its porous logic shall be exposed.

This brings us to the President’s decision to engage KPMG to investigate the SML affair.

Enter KPMG

Ordinarily, any referral of a raging controversy of this nature to technical experts ought to generate some relief. Yet, in this case, the President’s intervention sends mixed signals and can be rather counterproductive. Below, we list some reservations activists have raised.

The President’s action came after the matter had been referred to Ghana’s statutorily independent Office of Special Prosecutor, which has acknowledged receipt.

The President’s action attempts to pre-empt a parliamentary enquiry into the matter, and has been described as unwelcome by the Parliamentary Opposition.

The terms of reference issued to KPMG does not cover critical areas like the underlying procurement process and the essential logicality of the actual solution architecture.

There are broader issues of concern as well.

As everyone knows, KPMG, like the other Big Four professional services firms, is heavily exposed to public sector work in Ghana. It is the advisor to the government on its pandemic relief small business stimulus package. It is advising the GRA, which is at the centre of the SML storm, on the recruitment of technical and other staff to boost delivery capacity. It manages the ESLA tax vehicle on behalf of the government.

More to the point, it regularly pursues “revenue assurance” jobs from various government agencies, including the GRA. In some ways, therefore, it is a technical advisor to the GRA in some of the very areas it is being asked to investigate. It is also a competitor to SML in respect to some of the very areas it is being asked to investigate on it. Literally, all practice lines at KPMG are implicated in this assignment: audit, accounting, assurance/compliance and consulting. With only 12 partners spread across these practice lines as at last count, the idea of interlocking Chinese walls is simply impractical in an assignment of this nature.

In recent years, the complexities of confidentiality, conflict of interest, and political economy dynamics have made the involvement of Big Four firms in politically high-risk assignments fraught with reputational pitfalls. In Ghana, we saw the recent incident where GRA appeared to have built on initial work by KPMG to justify the hiring of a ghostly revenue assurance firm, Safari Tech, to trap telecom giant, MTN, a company that KPMG regularly serves (such as it did in MTN’s 2017 capital market transaction). That issue degenerated into a contentious mess involving the Ministries of Finance, the GRA, and the Ministry of Communications, leading eventually to what amounts to a political, rather than a technical, settlement.

In other jurisdictions with superior oversight and institutional maturity, such risks have exploded into serious blowouts. In the UK’s politically sensitive Grenfell Tower inquiry, KPMG had to step down over conflict of interest issues. In fact, protracted issues of a similar nature compelled KPMG to suspend further government work for a period in the UK and to even sell some of its business units in order to sustain public trust. In Australia, multiple confidentiality and conflict of interest abuses linked to public sector work have engulfed all Big Four firms, including KPMG.

Closer to Ghana, South Africa provides the most intense example of why Big Four firms should avoid becoming embroiled in politically high-risk assignments. KPMG was manipulated into whitewashing the Gupta cabal and assisting a faction within the Zuma regime fire a Minister they felt was obstructing the state-capture goals of the cabal. KPMG was abused by commentators as facilitating plunder and later lost lucrative client business.

This author cannot presume to lecture KPMG’s risk leaders on which public sector assignments to accept. The firm’s own global reckoning with politically sensitive work, however, counsels extreme caution. The SML assignment, judging by its terms of reference, and the timeframe of only two weeks, presents many slippery slopes for KPMG.

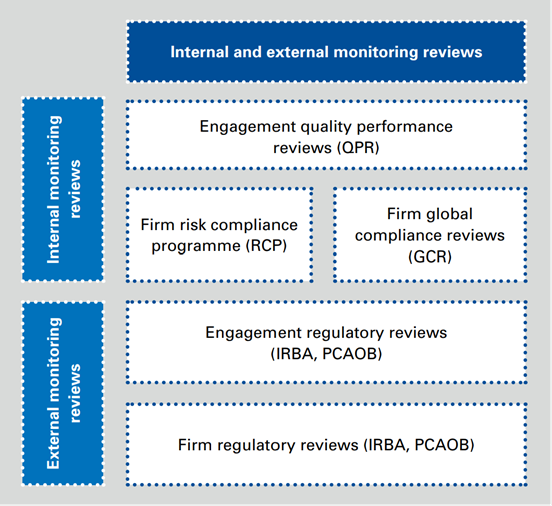

The firm’s In-Flight Review (IFR) framework, which requires partner-level interfacing at multiple rungs of an assignment, and different tiers of internal and external quality assurance, should preclude a rushed and cursory surface-skating over the many delicate issues raised in this essay in a mere two-week period.

Where these controls in KPMG’s public sector consulting work have failed around the world, the driving factor has invariably been the fraught pressures of the political economy, systemic conflicts of interest, and the relaxation of standards to meet unrealistic project goals and timelines.

There may well be a narrow role for KPMG in assisting statutory and/or constitutionally independent authorities, such as the OSP, Parliament, and the CHRAJ in conducting tightly narrow and highly technical studies on hyper-specific aspects of the SML affair, in ways that do not put KPMG in the position of “clearing” or indicting a client or competitor. That determination has to be made by the authority concerned, and in the pursuit of forensic goals only such authorities, and not a private entity like KPMG, truly have the lawful powers to pursue. We respectfully ask KPMG and the President of Ghana to support truly independent state agencies to delve into this affair without undue assumption of primacy or procedural interference.

A country that has just repudiated its debts and is in the middle of an IMF bailout program needs to demonstrate the highest levels of fiscal prudence. Unfortunately, this SML development and the handling of its aftermath threatens to further dent Ghana’s PFM credentials. It behoves on the government of the day to pull back from the brink whilst there is still time to salvage some scraps of PFM credibility.