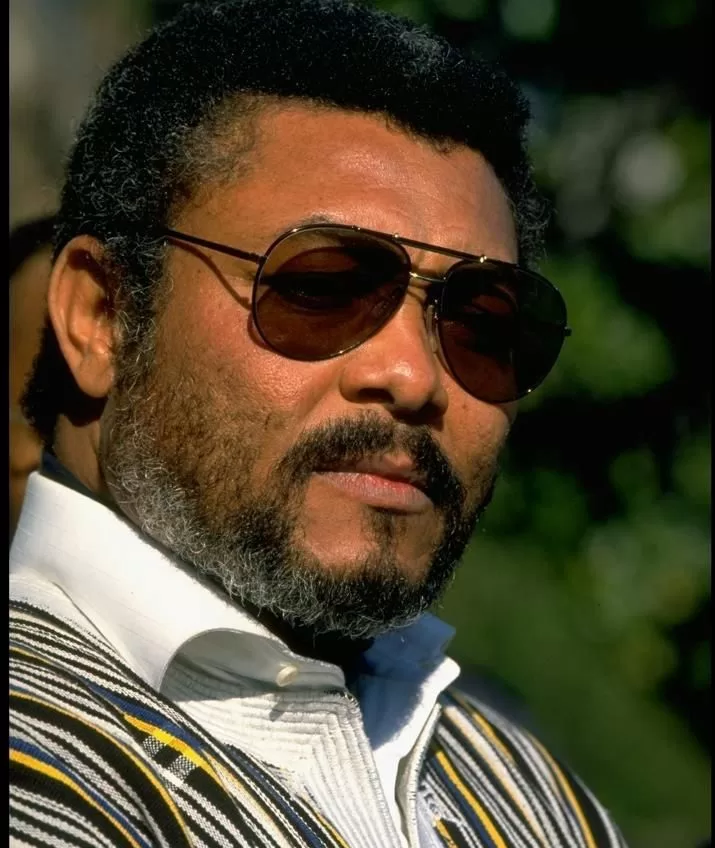

ALLENGES OF THE OFFICE OF THE SPECIAL PROSECUTOR IN FIGHTING CORRUPTION IN GHANA: BY MARTIN A. B. K. AMIDU, THE S. P.

The biggest challenge facing the Office of the Special Prosecutor as an anti-corruption investigatory and prosecutorial body in spite of all the powers conferred upon it is not the President who promised the people of Ghana to establish the Office but the heads of institutions who simply refuse to comply with laws designed to ensure good governance and to protect the national purse by fighting corruption.

Heads of institutions wantonly disregard statutory requests made by the Office for information and production of documents to assist in the investigation of corruption and corruption-related offences, in spite of the fact that the President has on a number of occasions admonished them on such misconduct. There have also been cases where some heads of institutions have made it their habit to interfere with and undermine the independence of this Office by deliberately running concurrent investigations falling within the jurisdiction of this Office with on-going investigations in this Office for the sole purpose of aborting investigations into corruption and corruption-related offences.

Some of the foregoing malfeasance has seriously affected the ability of this Office to deliver on its mandate, particularly when it must depend on some of these very institutions for seconded staff until it employs its own. The questions of anti-corruption work values and culture, and condoning indiscipline by some seconded staff by their parent institutions have surfaced and become public in some instances.

What is worrying to this Office as an anti-corruption investigation and prosecutorial agency is the refusal of heads of institutions to take steps to enforce basic rules of discipline governing their institutions even when they know that their officers are under investigation, have been cautioned, bailed, and eventually even charged with corruption and corruption-related offences.

The Civil Service, the Local Government Service, the Police Service, and other public services have specific laws and regulations governing what should happen to public officers who are under suspicion for disciplinary offences (including crime), and prosecution for crime generally which heads of institution ought to apply, without prompting, to fight corruption in their respective institutions. The Public Service Commission has also issued binding circulars and guidelines on ordering the interdiction and/or indefinite leave of public officers suspected of serious misconduct and the commission of criminal offences.

Unfortunately, the experience of the Office of the Special Prosecutor is that when it comes to fighting corruptions and corruption-related offences, heads of institutions think that the rules on interdiction and/or indefinite leave of public officers do not apply to corruption and corruption-related offences.

Public officers have been charged, arraigned before the High Court and their pleas taken only for them to return to their work places and work normally as though they have never been suspected of committing any corruption offences. In the first place an officer under investigation for misconduct or crime ought not to be in a position to interfere with the investigations. This explains the law and rules on interdictions even before a charge is actually preferred against a public officer.

The Office of the Special Prosecutor invites public officers to assist investigations through their heads of institutions and there can be no excuse after those officers have been publicly arraigned and their pleas publicly taken in a trial court for their heads of institutions to wait to be told what to do by way of disciplinary action pending the completion of the trial.

The Special Prosecutor has been accused of sleeping on the job when he has only three seconded investigators from the Ghana Police Service with no prosecutor employed directly by the Office for obvious bureaucratic and technical reasons. The Office has nonetheless managed to investigate and arraign a number of public officers before the High Court for prosecution, but their heads of institutions have failed or refused to apply the law on interdiction and/ or indefinite leave to deter others from following the same corruption path.

The Public Service Commission has an Appendix II in one of its circulars and guidelines on Public Officers on interdiction and/or indefinite leave. It is stated in (c) that: “During the permissible period of interdiction/indefinite leave, officers affected shall receive 50% of their monthly pay….” and in (g) it is stated that: “Responsibility for ensuring compliance with steps in (a) to (e) above rests squarely on the shoulders of institutional heads. If the institutional head defaults in this regard, their competent disciplinary authorities should impose on them sanctions not exceeding the value of the total loss to government or the employing organization, in terms of pay”.

What does the Government and the public expect the Office of the Special Prosecutor to do when heads of institutions refuse or fail to support the fight against corruption and corruption-related offences by not vigorously applying the regulations intended to aid the fight against corruption and other crimes? Corruption and corruption-related offences are offences committed primarily by public officers and one does not ordinarily expect heads of public institutions to protect public officers suspected of committing those offences even when they have been charged and put before the Court.

The two cases the Office of the Special Prosecutor has before the High Court for trial has surfaced the fact that heads of institutions do not take the fight against corruption seriously. This demonstrates that this Government’s fight against corruption has a long journey to go unless some drastic action is taken against defaulting heads of institutions as suggested by the Public Services Commission.

The perception that corruption and corruption-related offences are a systemic and pervasive low risk and high opportunity enterprise in Ghana was demonstrate beyond any reasonable doubt when the Office of the Special Prosecutor dared to charge and arraign before the High Court a member of the political elite (a Member of Parliament in this case) and some public officers for abuse of public office for private benefit and breaches of the procurement laws of Ghana.

A bi-partisan Legislature and the Executive machinery immediately invited the Special Prosecutor to commit to usurping the discretion of the Court by agreeing with Counsel for the accused on particular days for the trial of the case. The Legislature, whose members also form a majority of the Ministers in the Executive, went a further step in a bi-partisan manner to attempt to direct the Court in writing in the exercise of the court’s discretion to manage its own proceedings in the name of parliamentary immunity.

A country whose Parliament and Executive coordinate in Parliament in a bi-partisan manner to delay trials and justice within a reasonable time when it comes to prosecuting any of its members for corruption cannot seriously convince the outside world that it is not only paying lip service to fighting the canker.

The Office of the Special Prosecutor Act empowers the Office to enforce the production of information and documents in the Courts against any public institution that fails or refuses to honour the lawful request of the Office. This Office can also go to the High Court to compel heads of institutions to obey the laws that support the fight against corruption. The consequence will be that in accordance with the civil procedure rules this Office will have to sue the Attorney General as the representative of the State.

Those who know the history and character of the Special Prosecutor know that he is ready, able and willing to go this route should that be the only option left for the Office to effectively execute the anti-corruption mandate entrusted to him by the people of Ghana who supported his appointment. But let everyone remember when that day arrives there would be no bi-partisan praise for the Government – it will become a partisan political power play. Those who think this is talking too much or complaining too much should remember that a stitch in time saves nine.

The Office of the Special Prosecutor cannot fight corruption unless the public and civil society give it their fullest support and put pressure on the political elite to obey the laws that enable the Office to achieve its mandate. The President, the Minister of Finance, the Chief of Staff, the Auditor General, the Commission for Human Rights and Administrative Justice, and the Financial Intelligence Center have been very supportive of the Office thus far. But the response by other heads of institutions to the instructions from the Executive Branch appears to have been treated with impunity as far as the records show. Corruption cannot be fought on the so-called reputation of a few people. Every citizen needs to get involved now before the canker consumes the whole body politic.

DATED AT OSP, YENTRABI ROAD, LABONE, ACCRA THIS 15TH DAY OF JULY 2019

Source: 3news.com | Ghana]]>

ALLENGES OF THE OFFICE OF THE SPECIAL PROSECUTOR IN FIGHTING CORRUPTION IN GHANA: BY MARTIN A. B. K. AMIDU, THE S. P.

The biggest challenge facing the Office of the Special Prosecutor as an anti-corruption investigatory and prosecutorial body in spite of all the powers conferred upon it is not the President who promised the people of Ghana to establish the Office but the heads of institutions who simply refuse to comply with laws designed to ensure good governance and to protect the national purse by fighting corruption.

Heads of institutions wantonly disregard statutory requests made by the Office for information and production of documents to assist in the investigation of corruption and corruption-related offences, in spite of the fact that the President has on a number of occasions admonished them on such misconduct. There have also been cases where some heads of institutions have made it their habit to interfere with and undermine the independence of this Office by deliberately running concurrent investigations falling within the jurisdiction of this Office with on-going investigations in this Office for the sole purpose of aborting investigations into corruption and corruption-related offences.

Some of the foregoing malfeasance has seriously affected the ability of this Office to deliver on its mandate, particularly when it must depend on some of these very institutions for seconded staff until it employs its own. The questions of anti-corruption work values and culture, and condoning indiscipline by some seconded staff by their parent institutions have surfaced and become public in some instances.

What is worrying to this Office as an anti-corruption investigation and prosecutorial agency is the refusal of heads of institutions to take steps to enforce basic rules of discipline governing their institutions even when they know that their officers are under investigation, have been cautioned, bailed, and eventually even charged with corruption and corruption-related offences.

The Civil Service, the Local Government Service, the Police Service, and other public services have specific laws and regulations governing what should happen to public officers who are under suspicion for disciplinary offences (including crime), and prosecution for crime generally which heads of institution ought to apply, without prompting, to fight corruption in their respective institutions. The Public Service Commission has also issued binding circulars and guidelines on ordering the interdiction and/or indefinite leave of public officers suspected of serious misconduct and the commission of criminal offences.

Unfortunately, the experience of the Office of the Special Prosecutor is that when it comes to fighting corruptions and corruption-related offences, heads of institutions think that the rules on interdiction and/or indefinite leave of public officers do not apply to corruption and corruption-related offences.

Public officers have been charged, arraigned before the High Court and their pleas taken only for them to return to their work places and work normally as though they have never been suspected of committing any corruption offences. In the first place an officer under investigation for misconduct or crime ought not to be in a position to interfere with the investigations. This explains the law and rules on interdictions even before a charge is actually preferred against a public officer.

The Office of the Special Prosecutor invites public officers to assist investigations through their heads of institutions and there can be no excuse after those officers have been publicly arraigned and their pleas publicly taken in a trial court for their heads of institutions to wait to be told what to do by way of disciplinary action pending the completion of the trial.

The Special Prosecutor has been accused of sleeping on the job when he has only three seconded investigators from the Ghana Police Service with no prosecutor employed directly by the Office for obvious bureaucratic and technical reasons. The Office has nonetheless managed to investigate and arraign a number of public officers before the High Court for prosecution, but their heads of institutions have failed or refused to apply the law on interdiction and/ or indefinite leave to deter others from following the same corruption path.

The Public Service Commission has an Appendix II in one of its circulars and guidelines on Public Officers on interdiction and/or indefinite leave. It is stated in (c) that: “During the permissible period of interdiction/indefinite leave, officers affected shall receive 50% of their monthly pay….” and in (g) it is stated that: “Responsibility for ensuring compliance with steps in (a) to (e) above rests squarely on the shoulders of institutional heads. If the institutional head defaults in this regard, their competent disciplinary authorities should impose on them sanctions not exceeding the value of the total loss to government or the employing organization, in terms of pay”.

What does the Government and the public expect the Office of the Special Prosecutor to do when heads of institutions refuse or fail to support the fight against corruption and corruption-related offences by not vigorously applying the regulations intended to aid the fight against corruption and other crimes? Corruption and corruption-related offences are offences committed primarily by public officers and one does not ordinarily expect heads of public institutions to protect public officers suspected of committing those offences even when they have been charged and put before the Court.

The two cases the Office of the Special Prosecutor has before the High Court for trial has surfaced the fact that heads of institutions do not take the fight against corruption seriously. This demonstrates that this Government’s fight against corruption has a long journey to go unless some drastic action is taken against defaulting heads of institutions as suggested by the Public Services Commission.

The perception that corruption and corruption-related offences are a systemic and pervasive low risk and high opportunity enterprise in Ghana was demonstrate beyond any reasonable doubt when the Office of the Special Prosecutor dared to charge and arraign before the High Court a member of the political elite (a Member of Parliament in this case) and some public officers for abuse of public office for private benefit and breaches of the procurement laws of Ghana.

A bi-partisan Legislature and the Executive machinery immediately invited the Special Prosecutor to commit to usurping the discretion of the Court by agreeing with Counsel for the accused on particular days for the trial of the case. The Legislature, whose members also form a majority of the Ministers in the Executive, went a further step in a bi-partisan manner to attempt to direct the Court in writing in the exercise of the court’s discretion to manage its own proceedings in the name of parliamentary immunity.

A country whose Parliament and Executive coordinate in Parliament in a bi-partisan manner to delay trials and justice within a reasonable time when it comes to prosecuting any of its members for corruption cannot seriously convince the outside world that it is not only paying lip service to fighting the canker.

The Office of the Special Prosecutor Act empowers the Office to enforce the production of information and documents in the Courts against any public institution that fails or refuses to honour the lawful request of the Office. This Office can also go to the High Court to compel heads of institutions to obey the laws that support the fight against corruption. The consequence will be that in accordance with the civil procedure rules this Office will have to sue the Attorney General as the representative of the State.

Those who know the history and character of the Special Prosecutor know that he is ready, able and willing to go this route should that be the only option left for the Office to effectively execute the anti-corruption mandate entrusted to him by the people of Ghana who supported his appointment. But let everyone remember when that day arrives there would be no bi-partisan praise for the Government – it will become a partisan political power play. Those who think this is talking too much or complaining too much should remember that a stitch in time saves nine.

The Office of the Special Prosecutor cannot fight corruption unless the public and civil society give it their fullest support and put pressure on the political elite to obey the laws that enable the Office to achieve its mandate. The President, the Minister of Finance, the Chief of Staff, the Auditor General, the Commission for Human Rights and Administrative Justice, and the Financial Intelligence Center have been very supportive of the Office thus far. But the response by other heads of institutions to the instructions from the Executive Branch appears to have been treated with impunity as far as the records show. Corruption cannot be fought on the so-called reputation of a few people. Every citizen needs to get involved now before the canker consumes the whole body politic.

DATED AT OSP, YENTRABI ROAD, LABONE, ACCRA THIS 15TH DAY OF JULY 2019

Source: 3news.com | Ghana]]>

Full text: Martin Amidu writes about why his office is ‘failing’

Reading Time: 8 mins read

Recent Posts

- NPP accuses NDC of lawlessness, demands urgent re-collation by EC in disputed constituencies

- Anytime there’s vigilance, NDC wins – Malik Basintale

- Akufo-Addo statue in Takoradi suffers partial damage amid controversy

- Current financial year proving challenging for COCOBOD – IMF

- Agona West NPP expels Regional Minister, 282 others for anti-party activities

- Cholera outbreak in Western region claims 14 lives, over 800 cases recorded

- Sabotage allegations rock NDC in North Dayi: Akua Sena Dansua et al fingered

- “Re-collation and re-declaration” of winners at Police Training School in Accra illegal – NDC to EC

Popular Stories

-

Agona West NPP expels Regional Minister, 282 others for anti-party activities

-

Akufo-Addo statue in Takoradi suffers partial damage amid controversy

-

Current financial year proving challenging for COCOBOD – IMF

-

Anytime there’s vigilance, NDC wins – Malik Basintale

-

NPP accuses NDC of lawlessness, demands urgent re-collation by EC in disputed constituencies

ABOUT US

Newstitbits.com is a 21st Century journalism providing the needed independent, credible, fair and reliable alternative in comprehensive news delivering that promotes knowledge, political stability and economic prosperity.

Contact us: [email protected]

@2023 – Newstitbits.com. All Rights Reserved.