What is #prairiecore? Addison Nugent explores why fashion can’t get enough of the ruffles and romance of Victoriana – and its US equivalent.

From its beginning, Instagram was dominated by a certain look – a perfectly coiffed, immaculately made-up, Kardashian-type sensibility. However, around 2018, a new Insta aesthetic, named #prairiecore, emerged on the platform. Featuring fresh-faced young women with touselled hair frolicking through bucolic settings, wearing long, flowing dresses – the images stamped with the prairiecore hashtag are pretty much as far as you can get from the endless stream of models posing in bikinis at lounges in Ibiza. Gone are the sports cars, mansions, and diet pills, replaced by fairytale cottages, fluffy farm animals, and wildflowers. They evoke a time long past, before our obsession with wealth signalling and fast fashion, when artisanal craft and communion with nature were necessary parts of everyday life — the Victorian era.

#Prairiecore is not a one-off phenomenon. Again and again through the decades, fashion has cyclically returned to the Victorian influence. In fact, aspects of it can be seen across the fashion eras, from the hippy-dippy ‘70s, to the high-fashion ‘80s, the grungey ‘90s, the camp 2000s, and today. But why does the Victorian age, usually associated with uptight patriarchal values, have such staying power, and why do designers keep turning back to it for inspiration?

Queen Victoria is often seen as an austere figure. The young monarch who rose to power in 1837 at the tender age of 18, espoused deeply conservative values that included Christian morals, duty, seriousness, modesty, and ‘proper’ behaviour. During her reign, women began to shun makeup, and traded in the lush, pastel florals and frills of the early 19th Century for more sombre tones and higher necklines.

The Victorian era is arguably the most influential in fashion (Credit: Alamy)

In spite of its modest overtones, however, the Victorian era is perhaps the single most important inspiration for one of humanity’s most luxurious pursuits: fashion. “Victorian fashion is an amazing visual feast: besides the intense colours made possible by the first man-made dyes, there were extravagant patterns like cabbage roses, large-scaled botanically-correct brocades, William Morris acanthus leaves and every kind of paisley,” fashion historian Caroline Milbank tells BBC Designed. “It was a kind of golden age of trimmings: chenille fringe, jet beading, passementerie, embroidery, patchwork and appliqué, and lace, lace, lace”.

Movements like #prairiecore celebrate and romanticise home-spun values, while also suggesting a return to a rural idyll

Queen Victoria’s first and most lasting contribution to the world of fashion is the white wedding dress. When she married her cousin, Prince Albert, in 1840, she broke with tradition by donning a lily-white gown, shunning the ermine robe in favour of a look that said ‘wife’ and ‘virgin’ rather than ‘ruler’. Her marriage was the first true royal wedding, as we know it today: as an event offering a patriotic spectacle to help unite the people of Britain, with the monarchy inviting the public to participate in the festivities for the first time ever. She was paraded through the streets in a carriage, and as a result, white became standard wedding attire for brides, a tradition that has carried on to this day.

In the TV series Westworld, actor Thandie Newton wears costumes that reflect authentic prairie style (Credit: Alamy)

But the Victorian influence on fashion didn’t stop there, and her influence was also felt across the Atlantic. Queen Victoria had one of the longest reigns in British history, spanning 64 years, and during that time fashion changed constantly. In the 1840s, style was more subdued and English, whereas in the 1850s people were inspired by Empress Eugenie of France so more pastels and flower patterns came into vogue.

During the time of the American Civil War (1861-1865), which occurred in the middle of the Victorian era, textile production became faster and easier than ever before. Decades before, in 1801, the French inventor Joseph Marie Jacquard had created a device that increased the speed with which woven designs could be set up on a loom. This made it possible to create complex patterns that the classical draw loom could not accommodate. When factory power was added to this process, patterns that might have taken days if not months to weave could suddenly be produced in hours using minimal labour. As a result, beautiful patterns like paisley, complex florals, and bold plaid became more widely available. Alkaline or synthetic dyes were, however, only just coming into use, so the colours of the fabrics remained more muted, with dusty indigos, cornflower blues, rusty oranges, and brick reds.

In the 1870s frills and large crinolines became popular and the first bustle appeared. Then, in the 1890s the bustle was lost altogether, replaced by huge puffed or ‘mutton-sleeved’ tops. Many of these tenets lasted through the Edwardian period from 1901 to 1910 but ended completely post World War One.

By the 1920s, all remnants of the Victorian era had disappeared from fashion, as women started sporting sleeveless dresses with scandalously short hemlines and not a corset in sight. Then in the 1930s, designer Elsa Schiaparelli began making beautiful Victoriana-inspired pieces with puffed shoulders, intricate brocade, and long hemlines. Her aesthetics were at odds with the ultra-modernism of Gabrielle ‘Coco’ Chanel, and the two designers became fierce rivals and vocal critics of one another. In the end, Chanel’s modernism won the day.

Hippy chic

For decades, interest in Victoriana lay dormant — skirts got shorter, colours got bolder, and cuts more fitted. That all changed in the late 1960s when hippy women, who disagreed with the shallow consumerism of high fashion, began favouring looser clothing with longer hemlines. Brands like Gunne Sax began producing Victorian-style ‘prairie dresses’ adapted for the modern era. Gone were the corsets and crinolines, but the high necklines, puffed sleeves, and flounced skirts stayed. Founded during the Summer of Love in 1967, Gunne Sax was a departure from the tie-dye and psychedelic neons of the era, with its more neutral Civil War-era tones that would go on to dominate the 1970s.

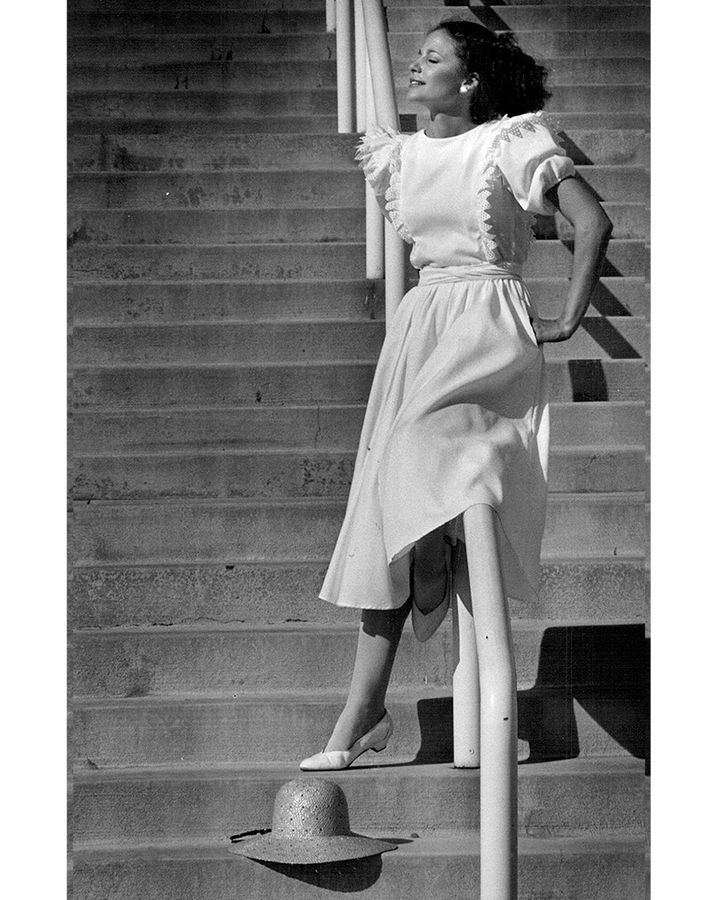

The Gunne Sax brand created Victorian-style ‘prairie dresses’ that dominated fashion in the 1970s (Credit: Getty Images)

Alongside the emergence of the prairie dress, there was also a shift from the mini skirt of the mid-1960s to the Victorian-inspired maxi skirt of the late ‘60s and early ‘70s. This period was dominated by civil rights movements including Women’s Liberation. During this era women began rejecting styles, like the miniskirt, that catered more to the male gaze than to female empowerment. The Victorian era, with its rejection of makeup and form-fitting clothing, may have appealed to hippies and feminists who viewed the fashion of the day to be shallow and consumerist. Frumpy prairie dresses and ankle-length skirts, once viewed as stuffy and conservative, were reclaimed as symbols of liberation. Hillary Rodham even wore a Gunne Sax dress for her wedding with Bill Clinton in 1975.

Model Stella Tennant photographed for Vogue in 2001 in an Imitation of Christ prairie dress (Credit: Getty Images)

The 1980s saw a return to supremely glamorous fashion. Bright colours and neon came back with a vengeance, and dresses got tighter than tight, with houses like Alaia introducing slinky body-con frocks. At the same time, however, the gigantic puffed sleeves of the 1890s made a return, notably worn by sartorial icons like Joan Collins and the rest of the fabulously camp cast of the soap opera Dynasty.

During the ‘80s the Laura Ashley dress, an even more accurate homage to the Victorian prairie dress than Gunne Sax, also became wildly popular, with the likes of Princess Diana sporting the brand. Laura Ashley fever continued into the 1990s when grunge rockers and riot grrrls paired the ultra-feminine frocks with Doc Martens and dark makeup. The grunge appropriation of Laura Ashley signalled yet another pendulum swing towards anti-fashion. The loose-fitting dresses with toned-down colors were a rejection of ‘80s extravagance and flashiness.

I am inspired by Victorian style because it offers a fantasy so different from our current world of athleisure – Batsheva Hay

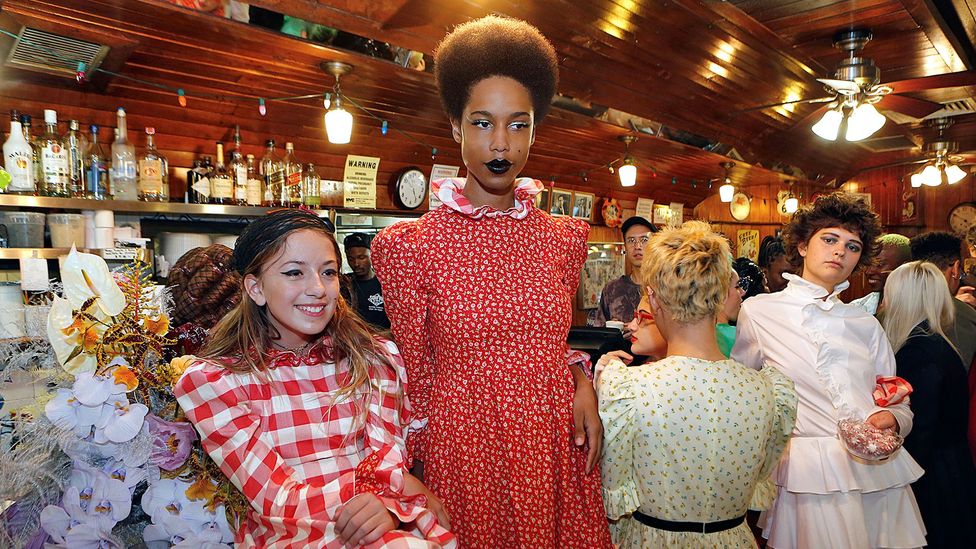

In 2018 designer Batsheva Hay took New York fashion week by storm with her romantic prairie dresses straight out of a bygone era. Everyone from Natalie Portman to Gillian Jacobs could be seen sporting Batsheva’s ultra-feminine modest frocks with Peter-Pan or piecrust collars, ruffles, and narrow bodices. The dresses became so popular that they sparked #prairiecore, which in turn sparked offshoots like #meadowcore and #cottagecore. “I am inspired by Victorian style because it offers a fantasy so different from our current world of athleisure.” explains Batsheva,” I love its soft femininity. I always like to dress with a sense of history and connection to the past.”

Designer Batsheva Hay’s spring/ summer 2019 collection is inspired by a sense of history (Credit: Getty Images)

The elegant puff-sleeved cotton and silk blouses that have been in vogue for the past few seasons are directly inspired by the early Victorian era. Today, women often pair them with blue jeans and chic heels, whereas in the 1840s blouses were worn with long full skirts and a thick belt. These blouses were high-necked and long-sleeved with a small round collar. The sleeves ballooned out around the forearm before coming to a tight cuff at the wrist.

Today, brands like Maison Cleo mimic the silhouette of the Victorian blouse almost exactly while adding modern twists like organza fabric and bold patterns. And original Victorian blouses are available from Vintage dealers like Maison Parisienne. “Today… people want to buy slow fashion more and more,” says Maison Parisienne founder Emma Moatti, “[and] the Victorian style is an echo to this idea.”

Perhaps in today’s climate of economic uncertainty people are turning away from the wealth signalling and obsessive accumulation of fast fashion, in favour of ethically-made artisanal pieces. Movements like #prairiecore celebrate and romanticise home-spun values, while also suggesting a return to a rural idyll.

Romantic styles at New York fashion week in 2018 helped spark the #prairiecore trend (Credit: Getty Images)

In a world that moves so fast, in which we are constantly bombarded with new information, the intricate artistry of Victorian fashion is a reminder of a time when the world moved considerably slower. “So much of what we look at now is on our phones. In miniature, the appeal of minimalism can get lost,” explains Caroline Milbank. “What pops and makes us want to look closer are interesting details. Ruffles and flourishes catch the eye. Styles reminiscent of long ago can lend a bit of romanticism to a mundane day.”