For sneakerheads, there is a style of trainer for every taste and identity. Arwa Haider explores the pop-culture currency of the footwear favourite, from ‘Satan Shoes’ to customised creations.

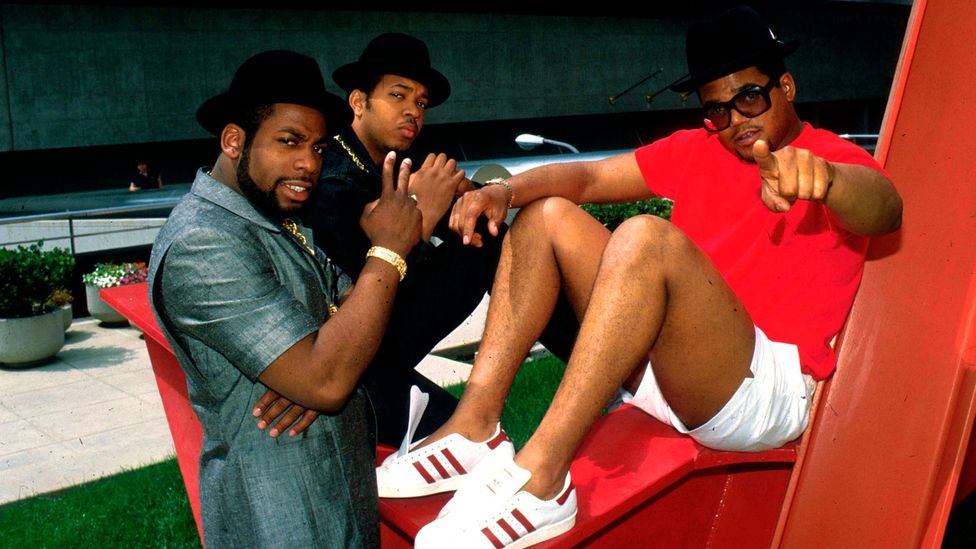

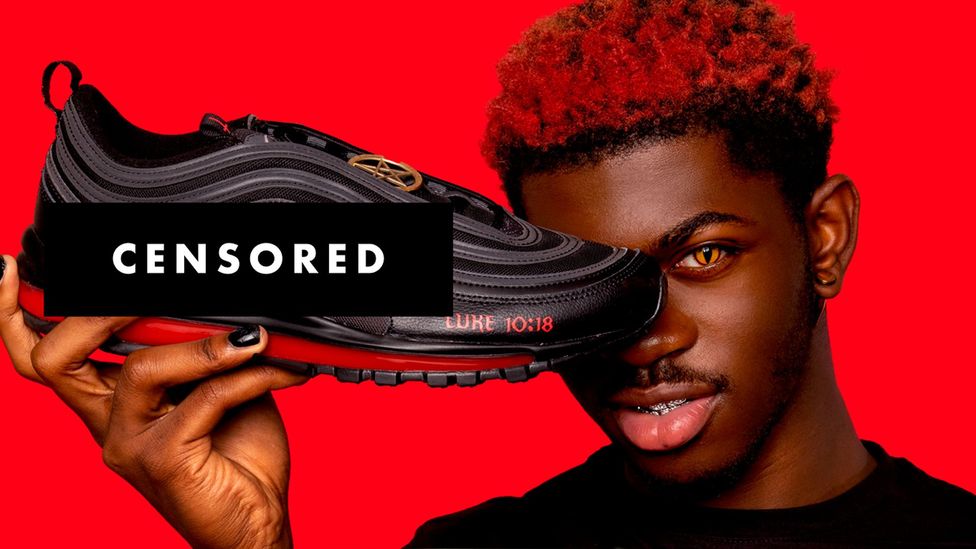

Boxfresh or battle-scuffed; on the court, the catwalk, or at the club or corner store – sneakers (or trainers, or sports shoes, or whatever you might call them) seem to enlace every form, function and fantasy – across sport, fashion, art, movies and music. Over several decades, sneakers have sealed their status as a pop-culture currency. In 1986, New York hip hop legends Run DMC created a ground-breaking anthem (and $1.6million brand endorsement deal) with their hit track My Adidas – and globally, sneaker statements and serenades have continued hard and fast since then, whether it’s Dr Dre displaying his pristine stash of Nike Air Force 1s, or Lil Nas X’s recent controversial/collectible “Satan Shoes”. London’s Design Museum has also dedicated its latest exhibition, Sneakers Unboxed: Studio to Street, to the footwear phenomenon.

“What appealed to me was to tell the story of sneakers in a design context as they are ubiquitous everyday designed objects that have taken on such great meaning in many people’s lives,” says Ligaya Salazar, the curator of Sneakers Unboxed. Salazar’s own fashion and art background, and time spent playing semi-pro basketball in her teens, echoes the exhibition’s multi-layered overview; the theme is handled with clinical precision (one of the opening exhibits dissects the “anatomy of a sneaker”), but also in a way that offers a vital emotional kick. Many of its defining images stem from street scenes and black cultural innovations; the show includes Martha Cooper’s vivacious early-80s photographs of NYC breakdancers sporting robust Puma Clydes; elsewhere, Grace Ladoja’s 2015 doc short Air Max – The Uniform explores the London grime scene’s favoured footwear.

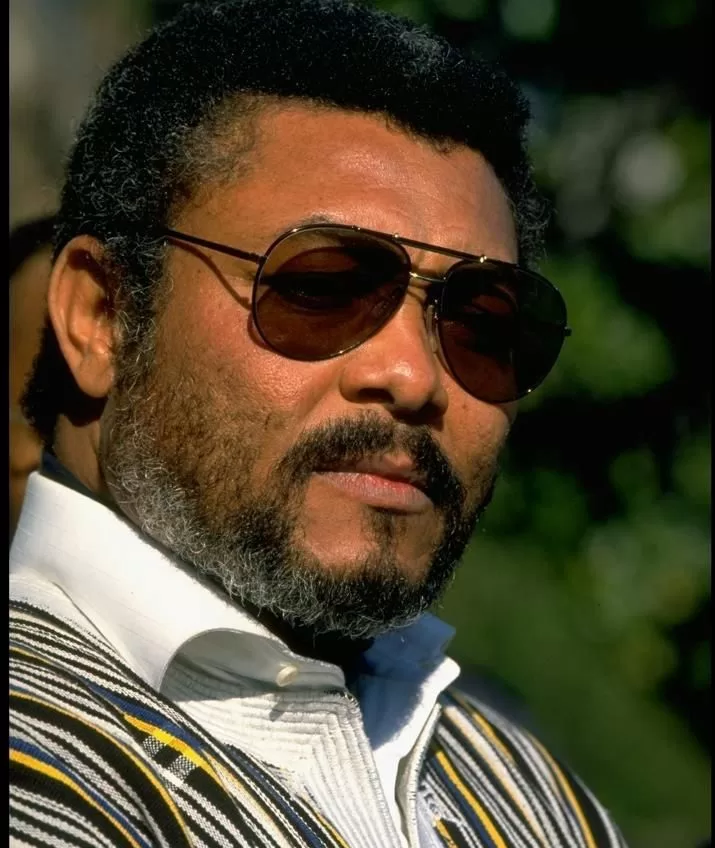

Ever since Run DMC’s 1980s hit My Adidas, sneakers have been both style statement and status signifier (Credit: Getty Images)

“Sneakers became style items and statements of identity at the end of the 70s, really,” Salazar tells BBC Culture. “It was a culmination of basketball (or football in the UK), style and youth culture that came together to form the foundations of what we now understand as sneaker culture.

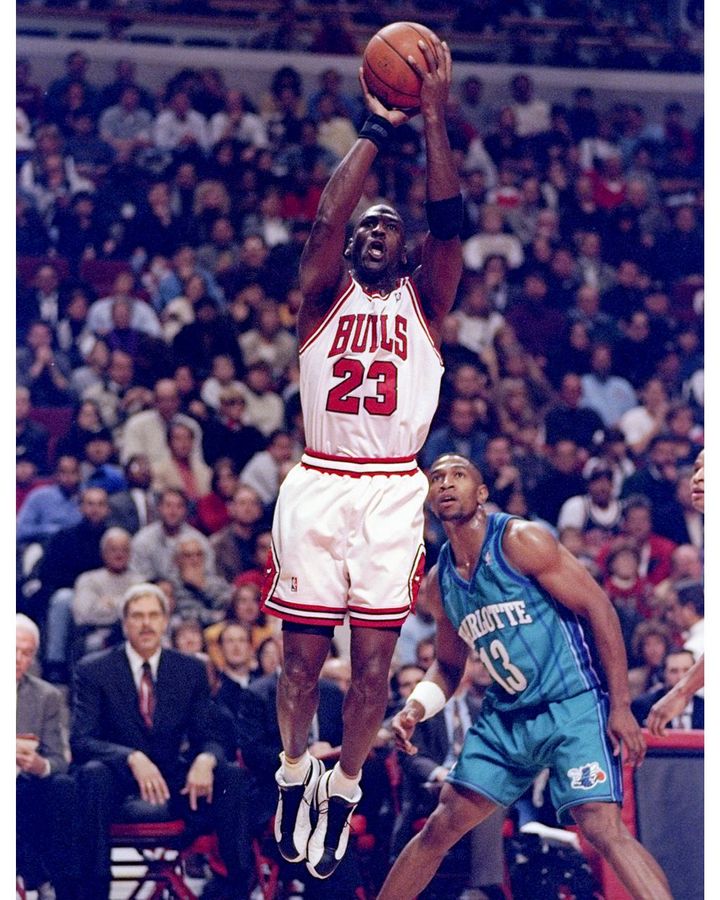

“Subsequently there are a number of events that cumulatively build on the popularity and status of sneakers: Run DMC being endorsed by Adidas (the first non-sports endorsement); the first reissuing of Nike Air Force 1s by three Baltimore retailers due to popular demand by customers; and, of course, Nike’s endorsement of young North Carolina rookie Michael Jordan – all in the mid-80s. This continues throughout the 90s before [the sneakers] get truly picked up by the big brands and resold as limited editions and collaborations, ultimately manufacturing exclusivity and desire.”

Nowadays, seemingly every pop culture event is heralded with rare-edition sneakers

There have always been powerfully opposing forces at play here, and they’re also rooted in youth culture: the urge to stand out, versus the need to belong (and swerve fashion mis-steps). At Sneakers Unboxed, I spot an immaculately cased set of Adidas all-white three-stripe Adicolor shoes (1983), designed as a “blank canvas” for personal customisation.

An exhibition at London’s Design Museum explores the sneaker as pop-cultural phenomenon (Credit: Design Museum)

It makes me recall the stress around wearing the “right” sneaker brands at my own schools in the late-80s and 90s. When I lived in Saudi Arabia, there was a peculiar vogue for pastel LA Gear shoes with criss-cross laces; when I moved back to South London, the footwear pressure intensified. I was heckled for wearing “foreign” (unrecognisable) shoes. Another girl at my secondary school was mocked for wearing plain non-branded trainers (we’d have never used the US term “sneakers”); keen to be accepted, she wrote “NIKE” in ballpoint capital letters on the sides – and she was bullied even more mercilessly after that.

When I think of my schoolmate’s trainers now, her DIY branding actually seems brilliant, yet filled with pathos. It also long predated the anti-cool artistry of Edmond Looi’s customised Adidas IKEA Ultraboost shoes (also displayed at Sneakers Unboxed) or the 2021 Tik Tok trend for simply-customisable “$15 Walmart sneakers”, as viewed on various viral dance clips.

I never belonged to a sports team or style tribe (Sneakers Unboxed highlights many fascinating examples, from British football “casuals” to Japanese collectors and Mexican “Cholombianos”, who combine sneakers with sacred iconography); pop culture shaped my sneaker choices. As a kid, I was drawn towards Converse All-Stars because of their association with multi-genre musicians, as well as their colourful range (the brand’s early-20th-Century founder Chuck Taylor set the tone with both his basketball skills and marketing prowess). There’s a seemingly infinite playlist of sneaker-inspired songs; US rap dominates, as showcased in Complex magazine’s 2013 feature, “The 50 Greatest Sneaker References in Hip Hop History” (including Nas, A$AP Rocky, Jay-Z, and obviously Run DMC), but French hip-hop crews also name-drop footwear, on moody tracks such as AirMax (2011) by L’Uzine from the outskirts of Paris.

The original Air Jordan sneakers were created exclusively for star basketball player Michael Jordan (Credit: Getty Images)

Certain sneaker songs defy street cred; on the country tune A Pair of Old Sneakers (1980), Tammy Wynette and George Jones lament a faded romance (“worn out an’ comin’ unglued”). More recently, the offbeat 2014 Mandarin-language track My Skateboard Shoes (translated lyrics: “I felt a force moving my feet/ With my skateboard shoes, I’m not afraid of the night”) scored brief viral success for its singer, Pangmailang. Elsewhere, shoes summon escapist magic in K-pop star Ha Sung-woon’s Sneakers (2021); in the video, he unboxes a pair of All-Stars that beautifully match his pink hair.

While pop culture connects sneakers with the international masses, an increasing focus on ultra-limited runs and luxury brands (such as Kanye West’s extravagantly-priced Yeezy line for Balenciaga) also transforms them into aspirational and untouchable items. Nowadays, seemingly every pop culture event is heralded with rare-edition sneakers – for instance, the Hacienda/Factory shoes to mark the seminal Manchester club’s 25th anniversary (2007, 250 pairs), designed by Peter Saville, architect Ben Kelly and bassist Peter Hook for Y-3 (Yohji Yamamoto/Adidas fashion collab).

Lil Nas X’s aforementioned “Satan Shoes” instantly became the stuff of legend: a limited edition run of 666 pairs of devilishly modified Nike Air Max 97s (reportedly with a drop of human blood in the sole) by art collective MSCHF, they prompted a lawsuit from the sportswear brand. Sneakers Unboxed displays MSCHF’s earlier “Jesus Shoes” model, containing “holy water” in the sole.

Musician Lil Nas X recently helped create the controversial ‘Satan Shoes’ (Credit: MSCHF)

“Artistic expression through customisation of sneakers has been intrinsic to sneaker culture from the start,” points out Salazar. “It is interesting that Nike chose to react to the ‘Satan’ version of the shoe and not the ‘Jesus’ one…”

Fuelling the mystique

Sneaker culture has appeared onscreen in feature documentaries including the star-studded Just for Kicks (2005), but fictional movies also fuel its mystique. When martial arts legend Bruce Lee wore Onitsuka Tiger sneakers in the early-70s, he kick-started the Japanese brand’s cult appeal; Uma Thurman’s costume homage in Quentin Tarantino’s Kill Bill Vol.1 (2003) would prove influential in its own right. A brilliant promo poster for Aliens (1986) declared: “REEBOK preview a shoe that you won’t see for 150 years”, with Sigourney Weaver’s sci-fi heroine wearing laceless “Alien Stomper” sneakers, designed by Tuan Lee (to a brief dictated by the film’s climactic scenes); fans would actually only need to wait 30 years for special-edition Alien Stompers – though the initial 2016 release bizarrely omitted women’s sizes.

Sneaker privilege isn’t only to do with how rich you are, but also your own status within the industry – Ligaya Salazar

In Back to the Future II (1989), Michael J Fox’s time-travelling hero wears hi-tech self-lacing Nike Mags; a 2016 edition of these sneakers is currently listed at £198,928 on resell site StockX. Space Jam (1996) had NBA high-flier and sneaker inspiration Michael Jordan hitting the court alongside Looney Tunes cartoon characters; LeBron James stars in 2021 sequel Space Jam: A New Legacy, which also yields a new gen of Nike tie-in shoes.

Sneaker culture has appeared on-screen over the decades, including Sigourney Weaver’s sci-fi, laceless ‘Alien Stomper’ trainers (Credit: Getty Images)

An intense level of detail makes certain sneaker designs seem like intricate delicacies; Chris Hill, Reebok’s senior manager of pop culture and streetwear collaborations, describes the “Classic Leather” series of Ghostbusters sneakers on the brand’s blog (October 2020): “People dress up in the [Ghostbusters] suits all the time, so this is sort of the shoe version of that… On the outsole, one of them has a glow-in-the-dark green spot like you stepped in slime. Then there’s a little hit of the yellow and black hazard stripe around the heel to spice it up a bit.”

Meanwhile, contemporary art immortalises sneakers as objects of desire – from German photographer Andreas Gursky’s vast-scale landscapes of Nike collections, to British artist Reuben Dangoor’s Holy Trainerty paintings.

Sneakerheads span the cradle to the grave: brands miniaturise their iconic designs as “baby cot booties”; while Accra-based coffin artist Paa Joe has crafted bright bespoke Air Jordan-shaped funeral caskets. Specialist apps track the giddying rate of new releases, while the impact of consumption raises questions in the modern world (Sneakers Unboxed also looks at ethical and sustainable production). Sneakers somehow remain all-encompassing, yet exclusionary.

Rare and limited-edition models are much sought after by avid collectors, or sneakerheads (Credit: Design Museum)

“There is a term increasingly used in sneaker culture that describes this perfectly: sneaker privilege,” says Salazar. “This privilege isn’t only to do with how rich you are, but also your own status within the industry. Online raffles should have made it more democratic, but there’s a big debate around people designing bots to hack the raffles and some sneakers not being fully distributed, so it is often still about who you know. However, if you are able to see through the ‘hype’ and aren’t in it to make money off reselling limited editions, there are a lot of interesting sneakers out there for every taste and identity. But it is definitely a very ‘coded’ world, where people judge you from your feet up.”

Sneakers Unboxed: Studio to Street is at London’s Design Museum until 24 October 2021.